Why I'm learning braille

and the social model of disability

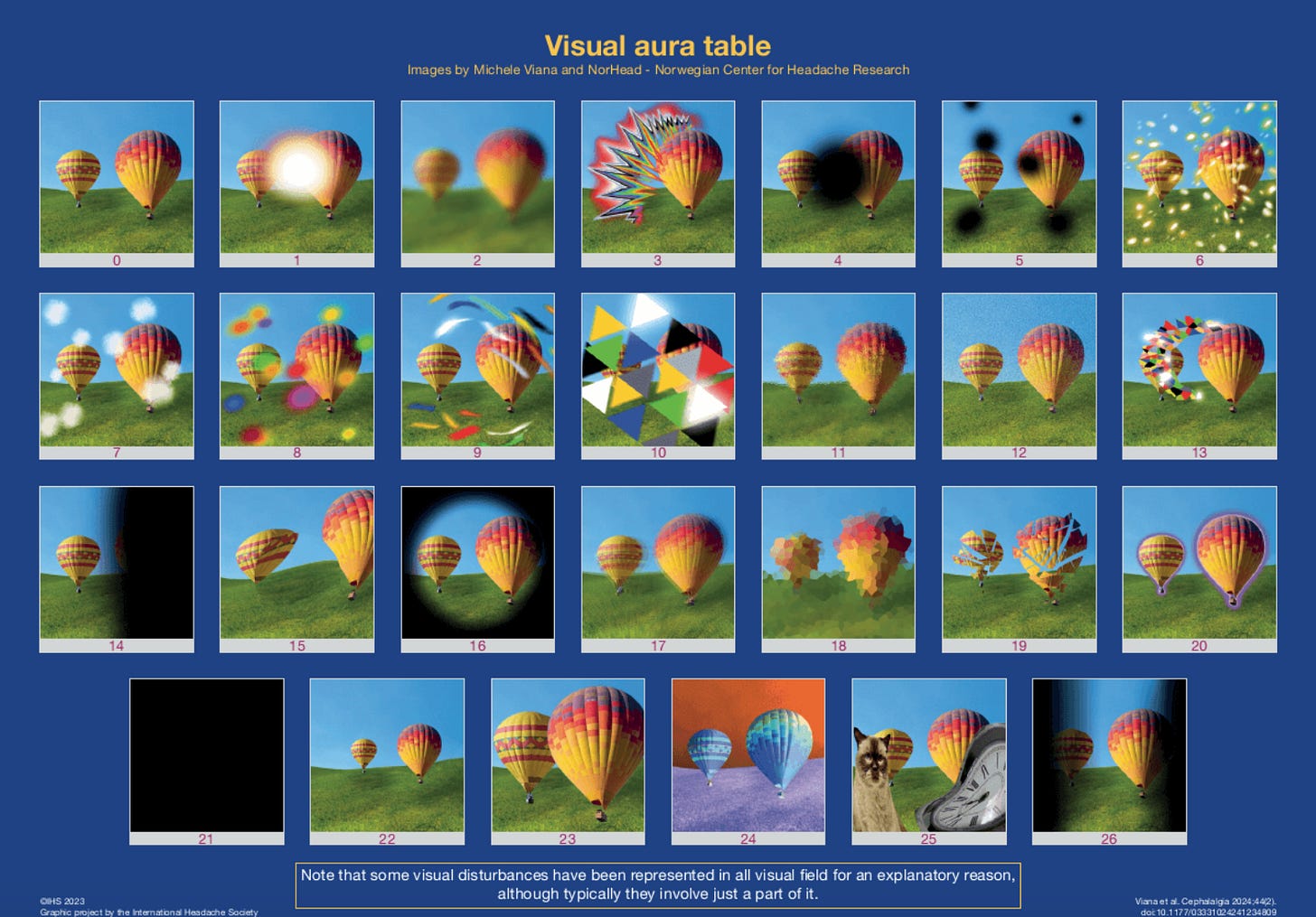

I waited over 9 months for my neuro-ophthalmologist appointment. It was minus 3 degrees outside and I travelled for over an hour to get to the hospital. For over a year, I had been having intense visual snow and persistent migraine aura with palinopsia and worsening Irlen’s syndrome. But I didn’t know it at the time. All I knew was that I had an appointment with a specialist and I was hopeful that I would get some answers as to why I couldn’t see properly anymore and get guidance on how to improve my visual processing.

The doctor got me to do a few tests and scanned the back of my eyes with various lights and magnifying glasses.

He then cheerfully said “great news, nothing is wrong with your eyes, you can go home now”.

I was shocked, I wasn’t able to read properly, if I moved my eyes too quickly, I fell over, my vision was incredibly blurry, pixilated and had multiple floaters. What did he mean nothing was wrong?

“Why do you want something to be wrong” his tone switched from cheerful to accusatory.

“I am very relieved I don’t have a brain tumour” I insisted “I’m just a little confused because I have lots of symptoms that are interrupting my ability to read and I was hoping to get some support with that”.

“We just support people with neuro-ophthalmological conditions” he said dismissively.

After multiple appointments where I have been dismissed by one doctor, only to be later treated urgently by a different doctor for displaying the exact same symptoms, I have become accustomed to advocating for myself in medical appointments and supporting my loved ones to do the same.

I got out my typoscope, a black piece of card with a long thin rectangle cut out of it, which you can lay over printed text and it allows you to look at just one or two sentences at a time, reducing the risk of visual overstimulation.

“I made this and it helps a little bit. I used to be a massive bookworm. You’re an experienced registrar at the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery. Every doctor I’ve seen has told me to wait for my appointment with you to get some answers. Do you have any advice you can give me to manage my symptoms?”

“Some people find large print easier to read” he tells me, clearly bored by our conversation.

I am full of despair, surely if I’ve gone to the trouble of getting a typoscope from the Royal National Institute of Blindness website, then I’ve obviously already tried large print. But I know if I reveal any emotions in this appointment, I’ll be branded as hysterical and my psychiatric history and my gender will be used against me to dismiss me.

“Do you think I should learn braille?” I ask, assuming I need a doctor’s permission for this or a referral to access lessons.

“No don’t be ridiculous” he replies.

“What would you suggest I do? What other support is available” I ask as my last attempt.

“Visual snow is functional. Wait to see the neuropsychiatrist” he says.

The appointment has clearly ended, and I reassure myself that I can cry in the taxi ride home.

I did end up seeing the neuropsychiatrist multiple months later and she referred me to a migraine specialist who diagnosed me even more months later with the conditions I mentioned at the beginning of this post. He reassured me that YES all my visual processing problems were because of my chronic hemiplegic migraines and NO unfortunately medication is not guaranteed to improve it as it is designed to target the migraine headache.

I will try and insert a simulation of what my vision has been like everyday for the past 3 years.

Now, you can probably imagine that it is incredibly difficult and nauseating to try and read while perceiving the world with this overstimulating, moving and blurry vision. Thankfully, 3 years later, now I’m on 8 daily migraine meds and receive regular occipital nerve block injections, my visual processing has improved, although it fluctuates, waxes and wanes. I can’t read for very long without giving myself a migraine. And whenever I have a migraine, my vision worsens for multiple days at a time. However, I can now (with tactical timing) actually read again! Thank God I got lucky with my meds, because there are only so many audiobooks someone with delayed auditory processing can take!

Anyways, now you know things have generally improved. Let me tell you about my decision to learn braille. There are a few different frameworks for understanding disability. There is a medical model which focuses on biological causes, pathological presentations and finding cures. Within this framework, something physical causes the body to malfunction and medicine has either already found a cure or is intending to create one if enough funding is allocated to scientists interested in that diagnosis. Through the medical model of disability, disability is a problem or deficiency within an individual which requires medical intervention.

This differs from the social model of disability. The social model of disability emphasises how societal barriers are the things that disable people, and if we lived in a world which was designed with accessible buildings, lacked discrimination and provided support, then disabled people would face fewer challenges and many would no longer identify as disabled.

Although my disabilities and health conditions would still exist and cause me difficulty in a perfectly accessible world, I generally subscribe to the social model of disability and find it incredibly helpful for understanding my experiences, creatively problem solving and discussing human needs with others. Thankfully I had long been a vocal ally to disabled people and had some understanding of different models of disability before I became/learned that I was disabled. This knowledge saved me plenty of time, heartache and struggle when navigating my sudden decline in health 3 years ago.

In addition, my previous plan for after graduating my undergraduate degree was to train as an Occupational Therapist. Unfortunately, I became very unwell in my final year of my undergraduate degree and am not well enough to meet the course demands of OT training. However, I had internalised enough of the OT approach, to supporting people in meaningful ways to occupy their time and in their acts of daily living, that I was able to, in many ways, be my own OT while adjusting to my physically, cognitively, socially and sensorily disabled life.

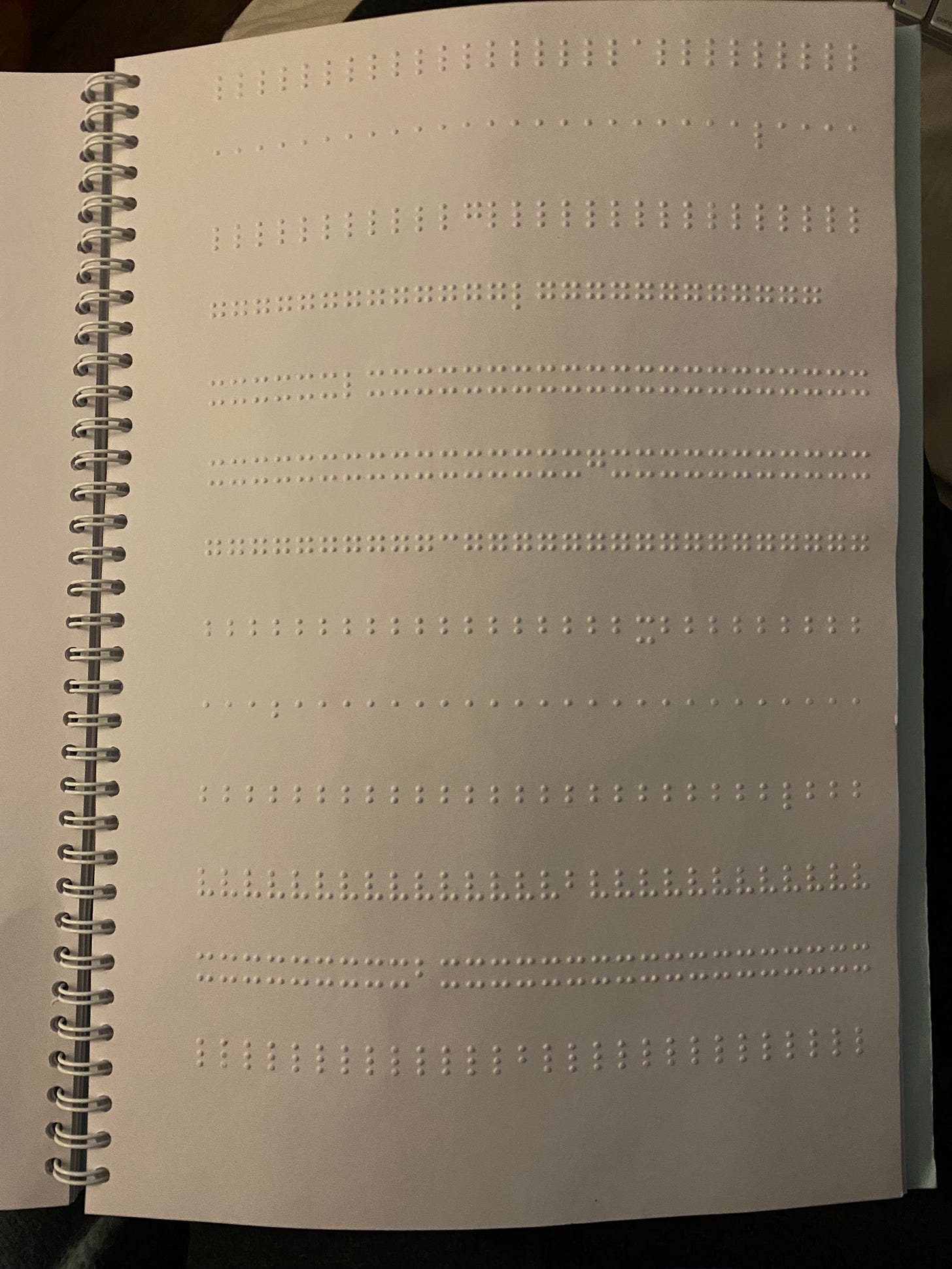

This is a long winded way of saying that when I accepted that I wasn’t able to read books without getting nauseous and giving myself a migraine, I approached this problem by at first defining the goal and then finding a creative way to adapt to meet it. My goal was to be able to take in information like stories without relying on my eyes or ears (as I’m fussy about narrator voices and I’ve honestly heard so many podcasts and audiobooks now that I just need some quiet time). This led me to consider learning braille, a method of taking in information by using your skin to detect little bumps on paper which, when combined, will signify words.

You might have noticed that I used the description of ‘skin’ rather than fingertips. This is because I am aware that some people with manual dexterity issues or who lack sensitivity in their fingers, have got around these challenges by using their lips to detect and read braille. Learning this fact gives me three very strong feelings in response.

1. I love humans

2. Disabled people are incredibly resilient and innovative, and I will forever be grateful for disabled community

3. Just because people without disabilities can’t imagine themselves coping with or overcoming a challenge faced by a disabled person, doesn’t mean disabled people can’t do it. (The same point stands on the topic of jobs. Just because you can’t imagine how a disabled person would do your job, doesn’t mean there aren’t any disabled people who can do it! You’d be surprised what we can do when given the opportunity and reasonable adjustments)

I had already contacted the RNIB for advice on screen reading software and using computers when your eyesight is unreliable, so I had some idea of what support and adaptive technology is available. Consequently, I also knew that the RNIB have a teach yourself braille set of self-guided course books. So, I bought them and have been gradually working through them.

Blindness is a spectrum and while I am not blind, nor would I describe myself as visually impaired, my vision is regularly disrupted by my neurological conditions. I could have accepted that I would never read again and that I must rely fully on auditory information or damage myself by trying to focus my eyes enough to read the occasional form or website in between the peaks of my daily migraines. But instead, I decided to expand my definition of reading and creatively problem solve by letting my abilities overcompensate for my struggles. Also, as a blessing in disguise, my loss of muscle and worsening joint pain meant that I had to give up playing the guitar, which meant that my fingertips lost their calluses and became sensitive enough to detect the braille bumps. Swings and roundabouts, aye?

Anyway, as I said, my visual processing has generally improved enough thanks to medication that I can occasionally read when my brain is not actively migrainous. I am still learning braille but at a more leisurely pace, because my eyesight is not reliable and besides, I think it is an incredible skill to have. Why are braille and Sign language not taught in all primary schools? I suspect kids would love to learn them!

Sometimes I wonder what my life would have been like if I just let that one doctor dictate how I approached my struggles with reading. I think I would have lost a lot of confidence, and my world would have shrunk. My daily life would probably contain more grief at the skills I had lost and I probably would have hidden my difficulties away from other people and been reluctant to bring it up to other doctors for further help. How many people do you think live like this? I suspect thousands of people have health symptoms that have been dismissed at some point in their lives so now they try to hide them, rely on unpaid carers or restrict their daily activities to get around the challenges their unsupported symptoms bring them.

Consequently, I believe doctors should be given more training on what it means to identify as disabled, what the social model of disability is and how disabled people can live fulfilling lives alongside their health conditions, impairments or differences. You’d honestly be surprised how many hospitals are absolutely not accessible to disabled people and how many medical professionals hold ignorant and harmful attitudes towards disabled people. Obviously not all are bad, but unfortunately most people I know have had at least one negative medical experience. I am incredibly grateful for peer support, experts by lived experience, and patient led initiatives. One example which springs to mind is the Visual Snow Syndrome initiative.

If you have ever, at any point in your entire life, asked someone or answered the question “would you rather be deaf or blind?”, I would like to challenge you to learn more about and donate TODAY to the Royal National Institute of Blind People, or the Royal National Institute of Deaf People, or both. These charities do incredible work filling in for the gaps in governmental and national support for Blind and Deaf people, and at some point in your life, either you or one of your loved ones may need them to guide you through something you currently can’t imagine yourself coping with.

Thanks for reading xoxo

I have written this post using a combination of speech-to-text software and manual typing so there may be errors. In addition, many of my neurological conditions impact my cognitive and linguistic abilities. But ultimately, as Casey Lewis said “all typos are intentional to make sure you’re paying attention” and I stand by that :)